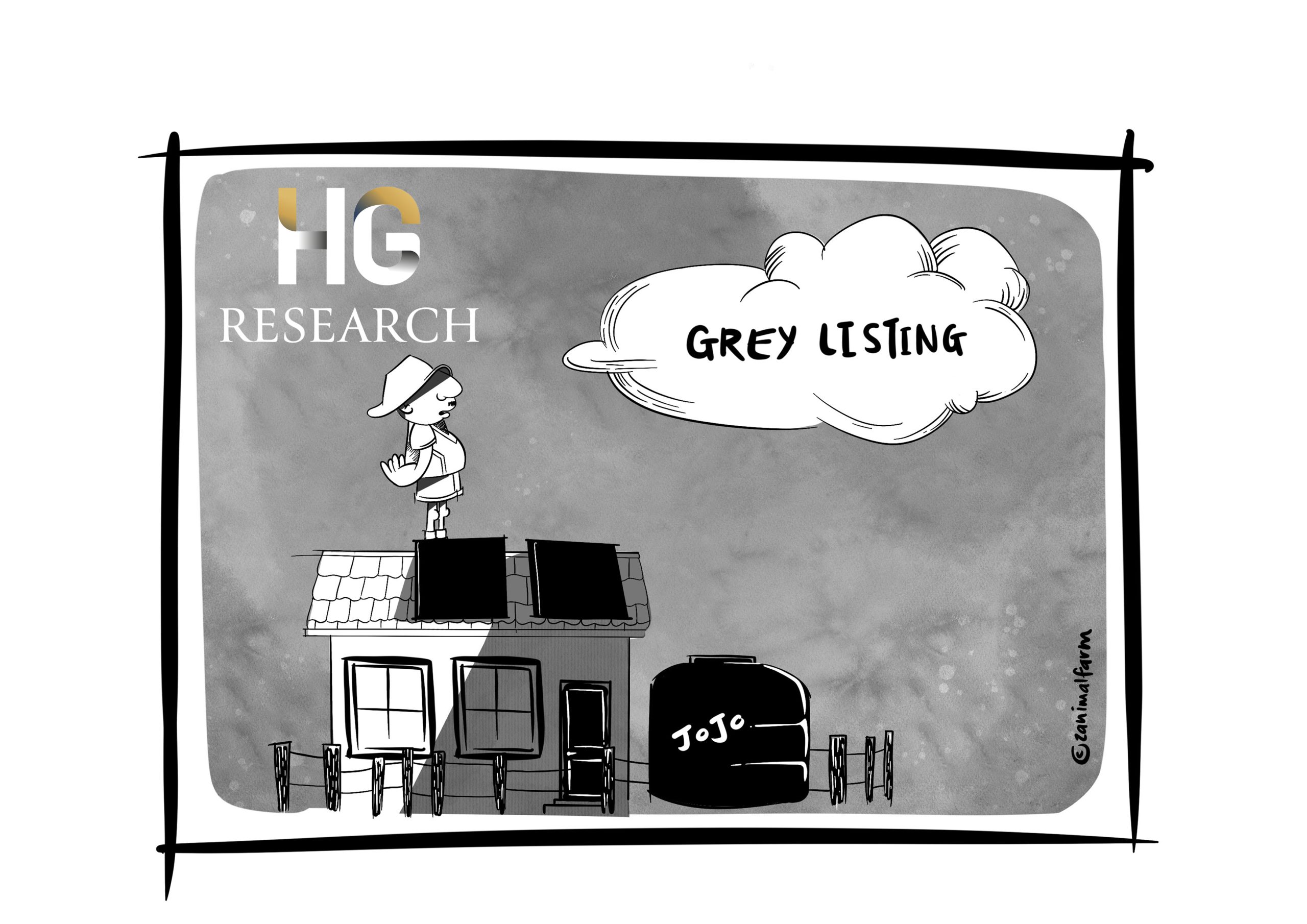

As of October 2021, South Africa is at risk of being placed on the grey list by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF). This news has inspired a fearful uncertainty as to the fate of our financial sector. And that of our retirement plans. What would being grey-listed mean for South Africa? Is there a way for South Africans to soften the blow? And what possible connection could exist between the FATF and a JoJo water tank?

In the 1970s rolling blackouts hit the United Kingdom. This brought the country to a near standstill. Hair was cut in the streets, university students were repurposed as firewood choppers and the government implemented a three-day workweek. Nothing close to this has been seen since. Except, of course, in South Africa. Daily. The only difference? Our hair salons run smoothly, our students are studying, and the 9-5 remains fully operational. One cannot mistake the resilience of the solar panel-bearing, electricity generator-wielding South African people. What of when the drought was announced in the Eastern Cape? Well, then we took up JoJo tanks, wells and, borehole water as naturally as irrigation specialists. The challenges that plague our country may be severe, but we continue to tackle each one ingeniously. South Africans are tough as nails.

Who is the FATF, and what does it mean to be grey-listed?

The FATF is a formidable body: the international watchdog on financial crimes. When this watchdog barks, you listen. Unless you’re a money launderer, then you run. Grey-listing means singling out a country for having poor protective measures against financial crimes. The grey-listed country is put under restrictions and closely monitored. As a watchdog, the FATF has sharp teeth. A country on the grey list is labelled a risky nation: its financial institutions are not entirely trustworthy.

How does this affect the average South African?

The effects will not be “felt” immediately by the average South African. There will be no FATF dog barking at your gate or gnawing at your shoe. It is more akin to a restaurant losing its food and safety rating – nobody wants to eat at a restaurant that has cockroaches in the kitchen!

Grey-listing plummets South Africa’s credit ratings, discourages foreign investment and ultimately stifles GDP growth. South African consumers will be directly affected by decreased employment, unfavourable exchange rates, and possibly higher inflation.

In 2021 the FATF began firmly biting at the heels of the South African financial system. If appropriate rectifications are not made, South Africa will be grey-listed by February 2023. The grey list cloud began gathering over South Africa when it fell into the clutches of state capture. State capture is right up there with load-shedding as a word we wish we didn’t need to know. When not used as a curse word, it is a form of corruption in which the private interests of individuals infiltrate the government. This means bribery. It also means money laundering: concealing the origins of money generated from criminal activity. These are financial crimes (queue barking noises). In its October 2021 report, the FATF argued that South Africa is not doing enough to proactively bring the state capturers to justice.

What does the FATF require?

The FATF listed 12 priority actions that were suggested to address this issue. These actions require a substantial, coordinated, and government-wide effort to implement. By October 2022, only 2 of the 12 priority actions had been satisfactorily implemented. The remaining actions are still being targeted. However, there are three other notable actions on which no notable progress has been made.

The failure to fix our ‘big three’:

1. Transactions across the borders

2. The Hawks

3. The private sector

is likely to be the nail in the coffin.

Are the important “Priorities” being addressed?

The borders. The first entirely unmet priority action is the required improvement in the effective detection of illegal transactions made across South African borders. Enhanced cash declaration systems have been proposed, but cash thresholds are yet to be set. Even if they were set, the national rollout of this would take time: something we no longer have.

The Hawks. Another failure is in the capability of the Hawks. The Hawks were created to deal with serious crime. They are the police of the state capturers. A natural assumption, then, if state capturers are still running around, is that the Hawks are not equipped to do their job. The Hawks have shown a failure to successfully investigate and construct financial crime cases. Building a capacity to do this and demonstrating its success to the FATF, once again, will take time.

The private sector: Finally, the FATF requires the scope of supervised business to be broadened to more non-financial businesses, such as gambling institutions. These businesses will be forced to comply with South Africa’s Financial Intelligence Centre (FIC) regulations. This is another priority action on which no notable progress has been made – it is expected to take two to three years before supervision will be effective.

South Africa’s fundamental problem is in the capacity and capability of its financial policing institutions. These organisations are short-staffed and overburdened. Without well-functioning institutions, it will be nearly impossible to achieve the 12 priority actions. To capacitate these institutions, we need time and resources. We currently have neither. This is why it is extremely likely that South Africa will be grey-listed in February 2023. If this news makes you want to climb into your JoJo tank and cover it with your solar panel so that you can float far, far away across the Atlantic Ocean – no judgement, we’ve all been there.

How do you prepare for this?

There is, however, a way South Africans are mitigating this, sort of like an electricity generator for grey-listing. Importantly, this alternative is not to stop investing altogether. Cashing the entirety of your wealth to store in your couch, although tempting, is not the solution. If our exchange rate decreases, imports will become more expensive and prices will rise. The money in your couch will not grow with inflation and you will be less wealthy. Instead, the smart alternative is offshoring investment: investing money outside of one’s home country. Choosing countries that do not face the same economic uncertainties significantly reduces your investment risk.

South Africans can take R11 000 000 out of the country annually (by applying for a foreign investment allowance), and it is easier than ever to do so. Just like solar panels have allowed independence from the Eskom schedule and JoJo tanks from the municipality dams, investing offshore is providing independence from SABC News. Giving a serious incentive for the government to end the misuse of its funds is beneficial for us all. South Africans are, however, showing that even this challenge is not insurmountable. We face clouds every day – all while maintaining our hair, educating our students, and working five days a week.

This is how you live in South Africa: Wealth, and income offshore, live by the coast with JoJo Tanks, and Solar Panels. Maybe start a backyard farm!